Sketchnoting: a spontaneous but needed reflection

2022-02-11 · About 6 minutes long

Preface

Since September of last year, I’ve been chipping away at a long-form post on how to take good notes. This, sadly, is not that post—consider this post a teaser to tide you over until then.

Today I finished my fourth book of sketchnotes. Each book has about 240 blank A5 pages, so I guess I’m fast-approaching the thousand-page mark. In celebration of filling yet another volume, I took a trip down memory lane and dug out Volumes 1-3. Taking the time to read through some of my older notes, it’s easy to see that I’ve improved quite a lot.

While reading through my second notebook, though, I found a short hand-written collection of my thoughts on note-taking. Although it’s been a few years since then, I feel like the core of what I had to say then rings true today.

Below I’ve typed up those few pages of notes, I hope you find them interesting:

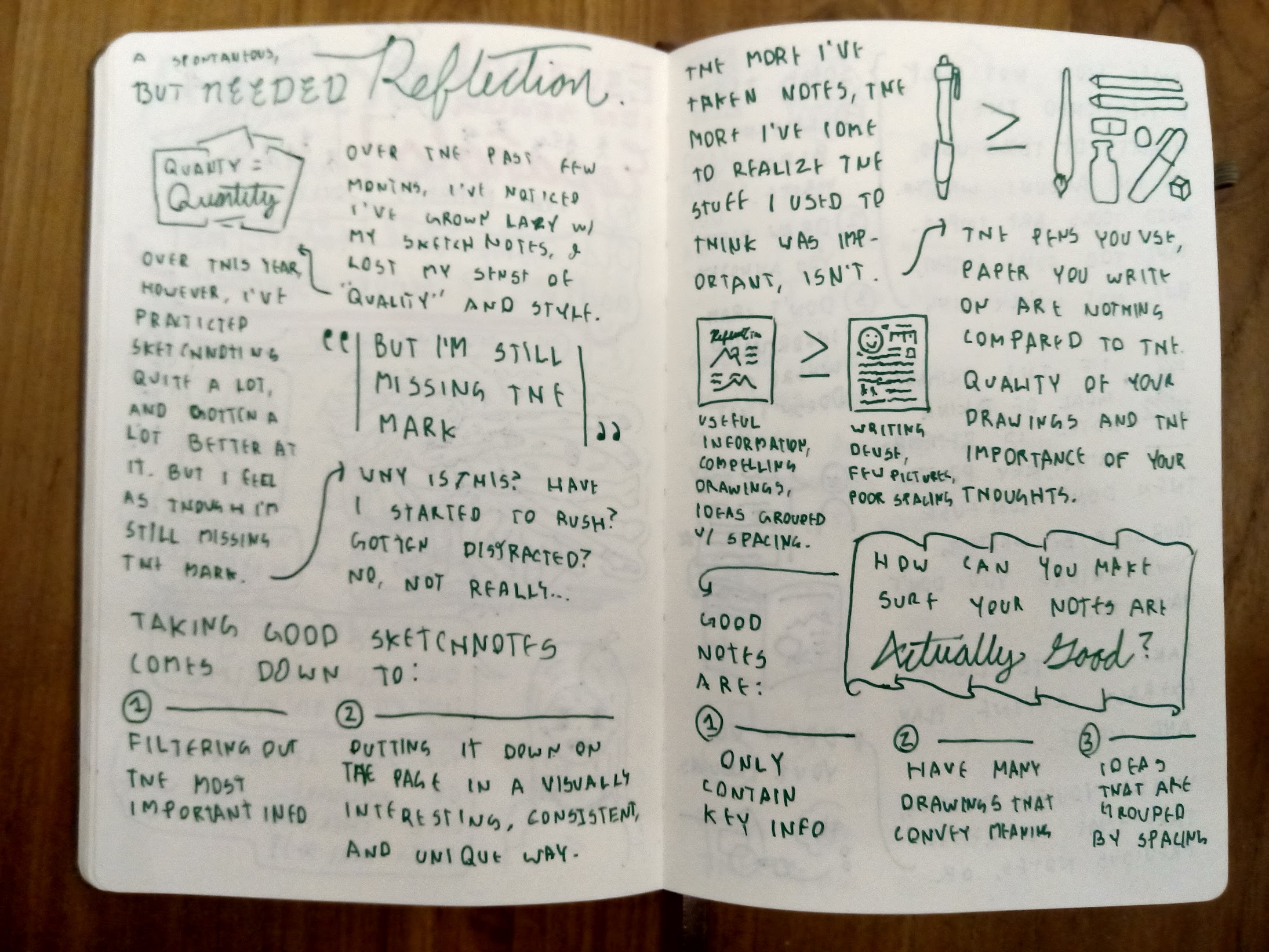

Quality and Quantity

Over the past few months, I’ve noticed that I’ve grown lazy with my sketchnotes, and lost my sense of “quality” and style.

Over this past year I’ve practiced sketchnoting quite a lot, and have gotten a lot better at it. Yet I still fell as though I’m missing the mark.

Why is this? Have I started to rush? Gotten distracted? No, not really…

What makes good sketchnotes?

Taking good sketchnotes boils down to two things:

- Filtering out all but the most important information

- Putting it down on the page in a visually interesting, consistent, and unique manner.

The move I’ve taken notes, the more I’ve come to realize the stuff I used to think was important isn’t. The pens you use, paper you write on are nothing compared to the quality of your drawings and the relative importance of your thoughts.

Structuring thought

So how should good notes structure your thoughts?

- Structure based on key information.

- Focus on drawing over writing.

- Leverage to medium, group ideas by spacing.

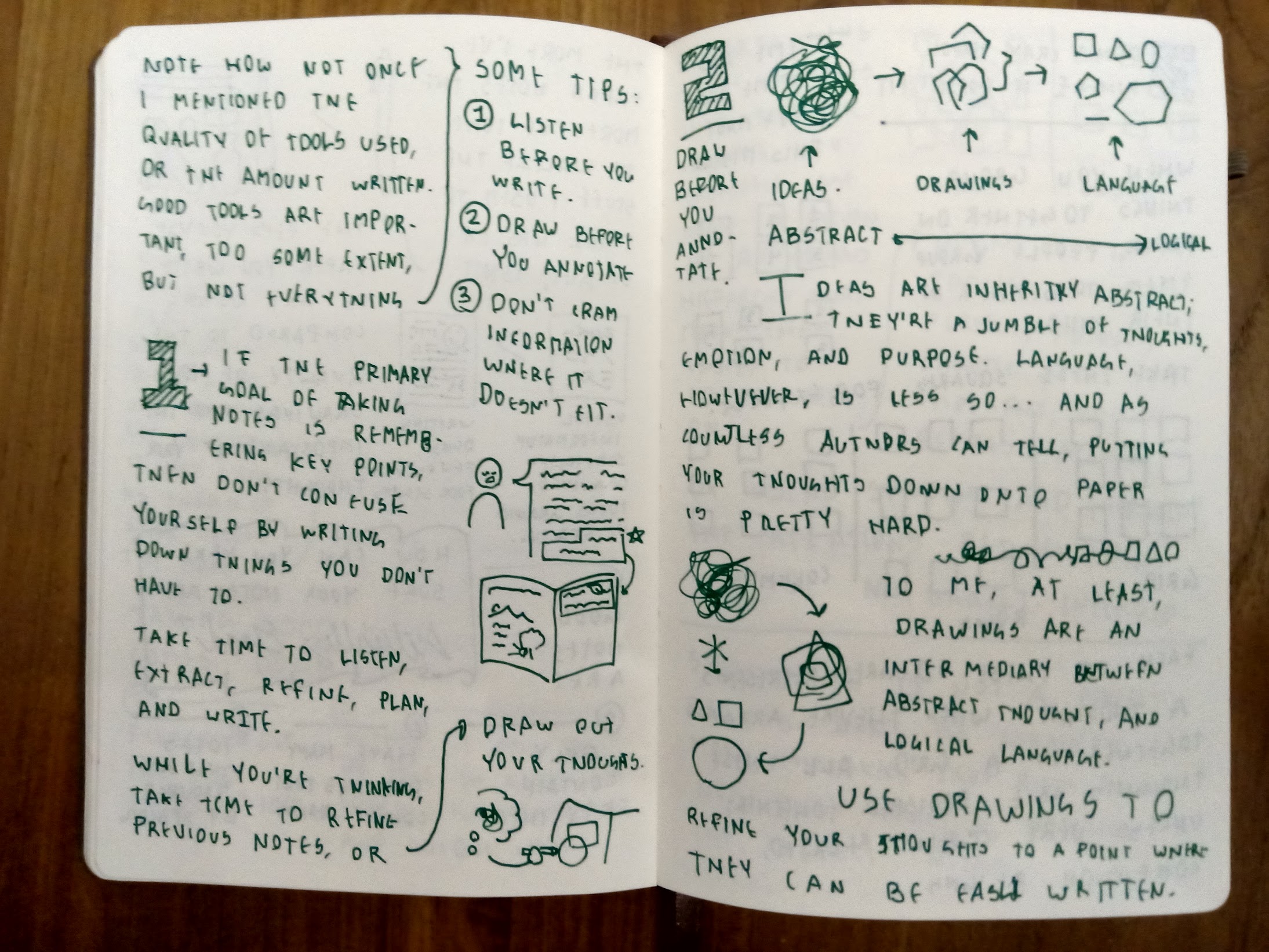

Note how not once I did I mention the quality of tools used, or the amount written. Good tools are important, yes, but they are not everything. So how can you accurately distill information? Some tips:

- Listen before you write.

- Draw before you annotate.

- Don’t cram information where it doesn’t fit.

How are these tips applied in practice?

① Listen before you write

If the primary goal of taking notes is remembering key points, then don’t confuse your future self by writing down things you don’t have to.

Take time to listen, extract, refine, plan, and write.

While you’re thinking, take time to refine previous notes, or draw out your thoughts on what you are currently listening to.

② Draw before you annotate

Ideas are inherently abstract; they’re a jumble of thoughts, emotion, purpose. Language, however, is less so… and as countless authors can tell you, putting your thoughts down onto paper is plenty hard.

To me, at least, drawings are an intermediary between abstract thought and formal language. Use drawings to refine your thoughts to a point where they can easily be written.

③ Don’t cram information where it doesn’t fit

Time and time again, I’ve made the mistake of mis-spacing elements. I’ll think about something I’d like to add and cram it into the margins, completely interrupting the flow of my notes.

Before you write anything down, think about how it will affect the layout of other elements on the page. When you group things together on paper, you form a visual hierarchy. People group nearby elements when reading notes.

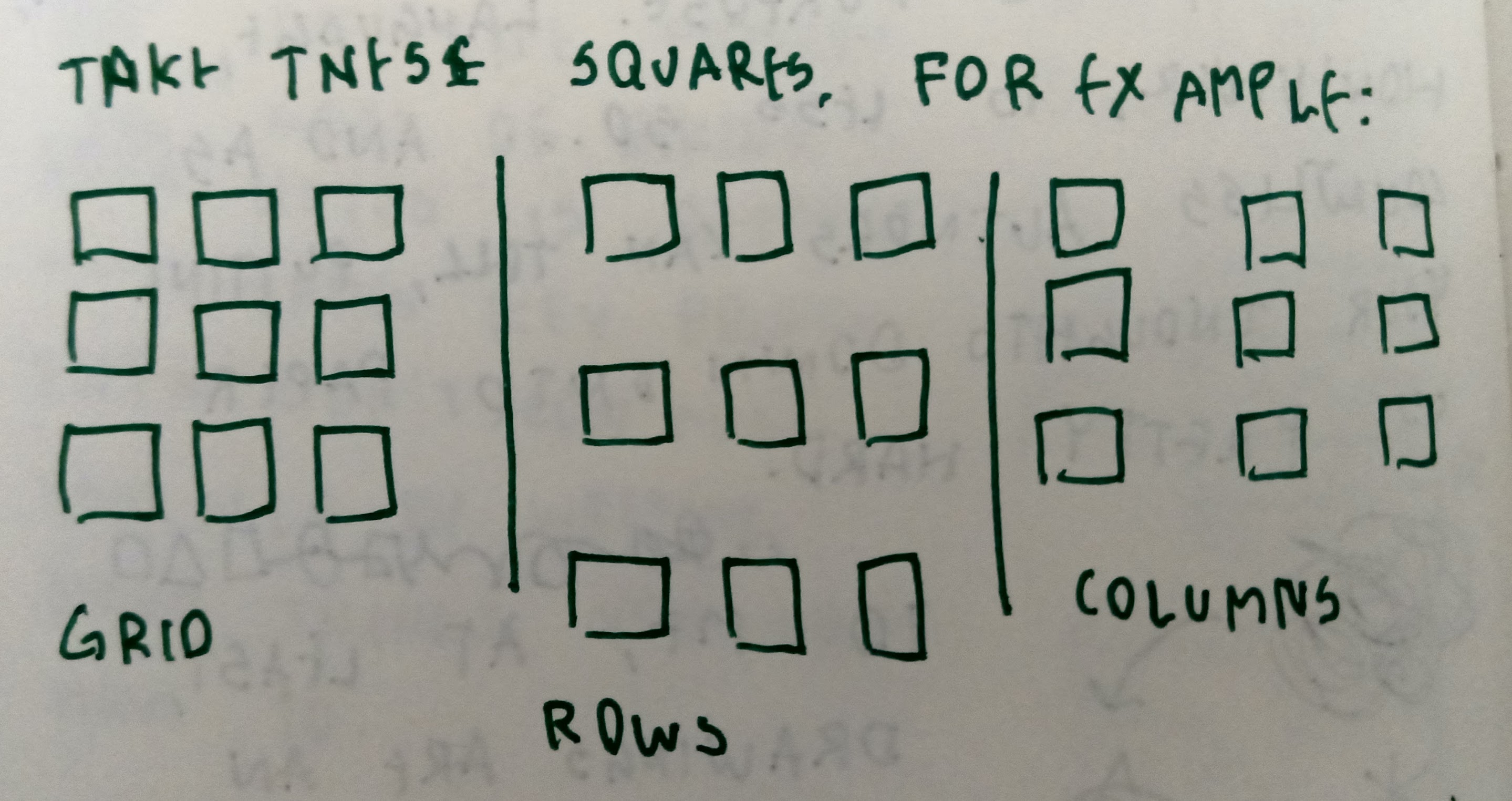

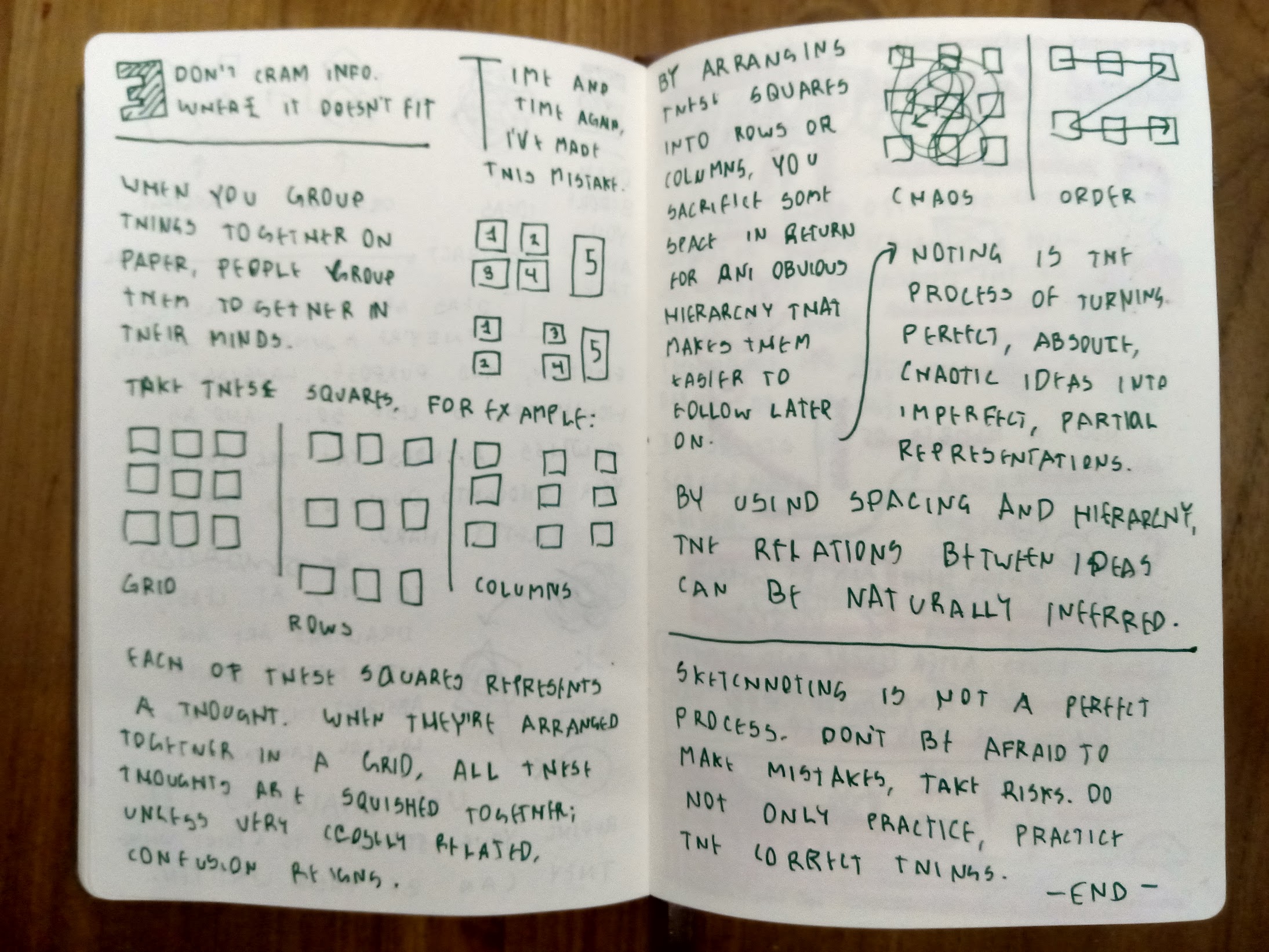

Take these squares, for example:

Each of these squares represents a thought. When they’re arranged together in a grid, all these thoughts are squished together. Unless very closely related, confusion reigns.

By arranging these squares into columns, you sacrifice some space in return for an obvious hierarchy that makes the progression of thoughts easier to follow later on. Note-taking is the art of turning perfect, absolute, chaotic ideas into imperfect partial representations. By using spacing and hierarchy, the relations between ideas can be naturally inferred.

Final Thoughts

Sketchnoting is not a perfect process. Don’t be afraid to make mistakes, as long as you make them correctly: take risks, learn from them. Do not only practice, but practice correctly: habits compound over time.

Takeaways

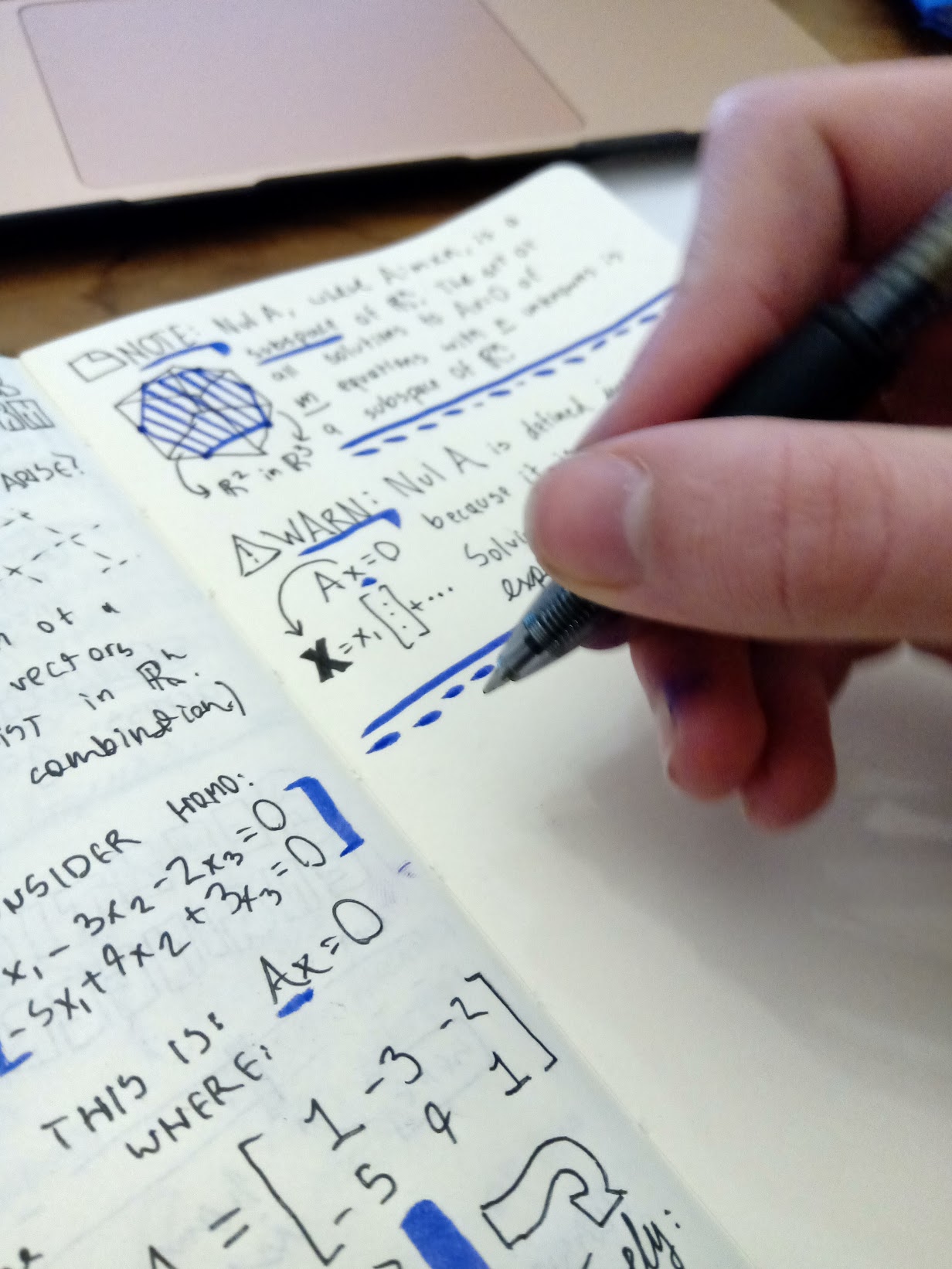

Recently I’ve been sketchnoting a lot of math (Linear Algebra and Multivariable Calculus). Compared to some other subjects, like english or history, math is a bit harder to sketchnote because it can be hard to come up with images that match the ideas you’re learning. Uncovering the underlying ‘story’ (usually obviously apparent in subjects like history) that links mathematical concepts is a harder challenge.

As I’ve sketchnoted more math, I’ve come to develop certain idioms and patterns that can be reused. Despite these notes being much better than the ones I took when first starting out, I feel as though I’m still missing the mark. I think that in the rush to capture everything, it’s easy to leave the core ideas out: the proofs and theorems that tie everything together.

Math aside, I think that what I noted about note-taking back then still rings true today. Good notes require active listening, distilling key concepts, then determining how to map those concepts onto a page. Skills learned through active note-taking make you more attentive and attuned to the world around you. There are lots of good guides to taking notes online, sure—but if you really want to get better at note-taking, there’s nothing more important than repeated practice and care.

So, what are you waiting for? Go take some notes!

Padded so you can keep scrolling. I know. I love you. How about we take you back up to the top of this page?