Vaporization and Modern Memory Management

2021-02-24

Note

This piece is a work in progress.

An interesting design space in the field of programming language design is that of memory management. In short, programs produce data while running. This in of itself isn’t much of a problem: in fact, it’s a good thing! If your programming language doesn’t allow for the production of any useful data, you might want to take a closer look at it…

As time goes on, our program may no longer needs certain data. We could just leave this garbage floating around forever, but, alas computers a finite amount of space to work with. It’s trivial to produce useful data; the more difficult task is figuring out when it’s no longer needed.

Originally, this work — the management of a program’s memory — was done by the programmer; older languages (like C) require memory to be explicitly malloced and freed.

While giving more low-level control to the programmer, the overhead of keeping track of all the lifetimes of data currently in scope is hard for a person to keep in their head, especially when slogging through some other tough, non-trivial problem.

In this post, we’ll take a journey through time and take a look at ways to manage memory. We’ll conclude by introducing Vaporization, a novel joint compile-time/runtime memory-management strategy that guarantees two things:

- Values are only alive where they are still useful.

- Data will be mutated in-place wherever possible.

But before we reach that point, it’s useful to have some background. And oh some background we will have:

Manual Memory Management

Words and RAM: What is memory, anyway?

If you’re already familiar with how memory management works, i.e. you’ve written some C or know what a pointer is, this next section will probably be very boring; just skip it.

To better understand memory management, we first must better understand memory.

Memory, in the broadest sense, is some hardware that data can be written to or read from. All computers ship with some amount of Random Access Memory (RAM), which is fast temporary memory used to store program state. My laptop, for instance, has a measly 4 gigabytes of RAM, whereas some higher-end desktops can ship with as much as 128GB (which I find disturbing).

RAM can be thought of as a very long list of addressed slots of the same size; on modern 64-bit computers, for instance, each slot stores 8 bytes, or 64 bits (hence the name). The number of bits a computer stores per slot is known as the word size of the machine.

In the following text, we’ll assume a 64-bit system, which I’d say are the most common today, and will likely be the most common for years to come: although 32-bit systems can only address 2^32 = ~4GB of memory, 64-bit systems can address 16.8 million terabytes, which is a metric-crap-tonne of memory. (Modern architectures usually limit this to something closer to a single terabyte, which is still a lot). Anyway, on a 64-bit system:

Each word can represent anything that can fit in that finite amount of space. These 8 bytes can represent whatever you like: an integer (from 2^-31 to 2^31), a double-precision floating-point number, or even another set of 8 bytes. You can do a lot with 8 bytes, but you can’t do everything.

I’ll refer use slots and words interchangeably, preferably sticking to the former. Although there are some slightly differing semantics, these two definitions are close enough for our purposes.

Structs

To build data-structures larger than 8 bytes, series of slots can be reserved. In compiled programming languages, these product-typed regions of memory are known as structs. Here’s a struct representing an (x, y) coordinate pair in good-ol’ C:

struct coordinate {

double x;

double y;

}

A double is an IEEE double-precision floating point number — it requires 64 bits of memory. Because this struct, coordinate, has two doubles, 128 bits of memory, 16 bytes, or two slots are required to store it.

It’s important to note that in theory, memory can be used however you’d like — In most cases, no higher-level representation is enforced by the operating system — a struct is just a convenient and reliably abstraction that we can use to talk about blocks of memory that span multiple slots, each slot (or group of slots) in that region referring to field in the struct.

Memory slots are required to be used in full, so structs are also padded to the nearest slot. For example, a C char is usually 8 bytes of memory.

struct char_pair {

char first;

char second;

}

struct char_number {

char letter;

double number;

}

char_pair would only take one slot to store on >16-bit systems, as the struct is 16 bits long. Likewise, on a 64 bit system, char_number would take 2 slots to store. Although it only uses 9 bytes of actual memory, the struct is padded to the nearest 8 bytes.

Optimization: Memory Alignment

Instead of storing values back-to-back, individual values are aligned to the nearest slot. Instead of layout out

char_numberlike so:CDDDDDDD D_______The compiler tries to align number to the nearest slot:

C_______ DDDDDDDDThis makes is faster to access individual values, as each field is stored in its own slot and no bit-twiddling has to be done to extract the data. Data can also be aligned along cache lines for even faster access, but that’s a bit out-of-scope at the moment.

Arrays

The primary issue with structs is that they’re static; once one is constructed, it can’t grow in size. This isn’t much of an issue for values that rely on a constant number of bits, but it is a large issue when a variable-sized collection datum needs to be kept.

To allocate multiple values, we can allocate a region of memory of a certain size. These arrays are inherently statically sized — an array can only hold the number of items it is allocated with — to store a larger number of items, the a larger array needs to be reallocated.

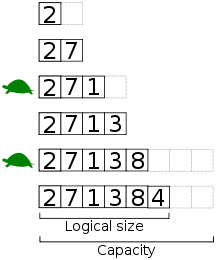

A dynamically sized array (a vector), common in most programming languages (such as Rust, Python, or whatever-have you), is simply a wrapper around an array that automatically reallocates it to the needed size as more values are added or removed. These allocations occur as the array grows or shrinks by an order of magnitude.

“Several values are inserted at the end of a dynamic array using geometric expansion. Grey cells indicate space reserved for expansion. Most insertions are fast (constant time), while some are slow due to the need for reallocation (Θ(n) time, labelled with turtles). The logical size and capacity of the final array are shown.”

— Wikipedia

Pointers

The main issue with vectors is that they can take up a variable amount of space. If you tried to cram a vector directly into a struct, for instance, the entire struct would have to be reallocated along with the array.* In this case, it’d be much easier to describe where the array is than *what it contains.

*Of course, this doesn’t really make much sense, which is why it’s not possible.

As memory is simply a long series of slots, to reference another location in memory, any slot can be referenced by its index. This index, or pointer, is usually less than or equal to the slot size of the architecture.

So, for example, the structure definition of a dynamically sized vector of doubles might look like so in C:

struct vector {

int capacity;

int count;

double* doubles;

}

* in c represents a pointer to another location in memory. Because pointer and int are both usually the size of a machine word, this struct will only take up 3 slots, even if it contains millions of values.

Aside: Linked Lists

Pointers can reference any location in memory, including other structures. Another way to implement a growable collection of elements is to use a linked list A linked list is a structure that contains a pointer to the next node in memory:

struct link { link *next; double item; }The above is a singly-linked list of

doubles. To add an item, construct a newlinkand update next to be the a pointer to thatlink.

Tagged Unions, i.e. Enums

As you know at this point, a struct is just a region of memory, where different slots correspond to different fields. It’s possible to make a struct that can represent different types of values: this sum-typed region of memory is is known as a tagged union or enumeration in most programming languages - here’s one in Rust:

enum Size {

Small {

one: usize,

},

Big {

one: usize,

two: usize

},

}

For the uninitiated, in Rust a

usizeis an unsigned integer the size of a word. The following is mostly Rust-specific, but the concepts can be applied generally:

Size can be one of two structs: Size::Small, or Size::Big - each of these sub-items is known as a variant. Small contains a single usize and is therefore only one slot big, whereas Big contains two usizes, and is therefore two slots big.

How does the computer we know which struct we’re talking about, though? Given a reference to Size, how can we determine which variant it is?

The usual solution is to store a hidden field, called the variant tag, which is a number (usually a byte) that points out which variant we’re referring to. 0x00, for instance, could be Small, and 0x01 could be Big.

Pro-tip: this is why it’s called a ‘Tagged Union’ ;).

An enum takes on the size of its largest variant, plus a byte for the variant, padded out to the nearest word. Following this logic, we can easily see that Size should be 3 slots large: 2 slots because of Big, 1 for of the tag (+ padding). In memory this looks something like so:

T_______

XXXXXXXX

XXXXXXXX

Where T is the tag, and X are either variant.

The Anatomy of the Program

After that grueling section, We’ve finally finished the appetizer and started the first course. From here on out, I assume you’re comfortable talking about memory. (Later, we’ll introduce a few new concepts, such as reference counting and Copy-on-Write pointers.)

When a program is run,

The Stack

The Heap

What is Garbage, Exactly?

Data Lifetimes

Problems with Data

Use-After-Free

Dangling Pointers

Memory Management Strategies

At this point, we’ve covered how m

A Simple Example: Reference Counting

A Not-so-Simple Example: Cycles

Aside: Breaking Cycles

Garbage Collection: Taking Out the Trash

Aside: Functional Programming and Persistent Datatypes

Compile Time Garbage Collection

Borrow Checking

Compile-Time Paths

Aside Generational Arenas

Vaporization

You’ve made it! you’re finally here! Now that we understand what memory is and how we manage it, I’m going to introduce Passerine (a novel programming language) and Vaporization.

Vaporization boils down to a set of compile-time optimizations that ensure that only useful data is accessible through the lifetime of the program, with minimum support for the language runtime. However, a runtime is still required, so Vaporization remains more suited to interpreted languages.

What’s most interesting about this, however, is that this system requires minimal interference from the compiler when used in conjunction with a VM. All the compiler has to do is annotate the last usage of the value of any variables; the rest can be done automatically and very efficiently at runtime.

Vaporization is an automatic memory management system that allows for Functional but in Place style (we’ll get to this) programming. For Vaporization to work, the compiler makes the following invariants hold:

- All functions parameters are passed by value, via Copy on Write reference (CoW).

- A form of SSA is performed so that the last usage of any value is that value itself, and is not CoW reference to that value.

- All values captured by closures are immutable.

- All functions must return a value that is not CoW.

We’ll work through each of these rules and various examples in the following section to build an intuition as to why Vaporization works. Afterwards, we’ll write a semi-formal proof as to why this holds, and discuss Vaporization’s tradeoffs and limitations.

What is Copy on Write?

A copy on write reference (CoW) is a pointer to some immutable data, that when written to, is copied to a new memory location first.

Let’s develop a better intuition for how this works. Say we have a struct that looks like this. I’ll use Rust* for this example:

use std::borrow::Cow;

struct Thing {

first: usize,

second: usize,

}

fn change_first(

thing: &mut Cow<Thing>,

value: usize

) {

if value > thing.first {

// clone thing on write

thing.to_mut().first = value;

}

}

fn main() {

// make a Cow reference to a `Thing`

let thing = Thing {

first: 420,

second: 69

}

let ref = Cow::from(&thing);

// 100 is less than 420, so no copy is made

change_first(&mut ref, 100);

// 9000 is over 420, so copy is made

change_first(&mut ref, 9000);

}

* Rust technically calls this a ‘Clone on Write’, because ‘cloning’ (deep copy) and ‘copying’ (memory copy) have slightly different semantics. Luckily both ‘clone’ and ‘copy’ start with a ‘c’, So I’ll just be referring to the general concept as ‘CoW’.

That was a big example, but there are basically a few things to take away:

- When we pass a

Cowreference to a function, no copy of the wrapped value is made. - Only upon writing to the thing (

thing.to_mut().first = value) is the copy made.

This means that the immutable data wrapped in the Cow is safe, and can not be mutated - yet functions can mutate the reference, producing new useful values.

Passing by Value with CoW

Passerine, unlike Rust, does not allow for pass-by-mutable-reference* (that’s what the &mut means) — instead, Passerine is completely pass by value. If we approach pass by value naïvely, it’s tempting to make a copy of every object before it’s passed to a function. However, if we have a million-element list, imagine what havoc that could wreak:

-- this is Passerine, by the way

-- I'm using this as a notation for a big list

-- just note that the items are elided

big_list = [ ... ]

for _ in 0..100 {

-- some function that just reads `big_list`

print (conswizzle big_list)

}

If a copy of big_list were made every time it were passed to conswizzle, 100 copies would be made! That’s no good for performance!

Aside: Pass by Value vs. Pass by Reference

Pass by value means that when you pass something to a function, that function only has the value itself to work with. For example, if we have:

set_to_2 = n -> { n = 2 } x = 3 set_to_2 xThe

n = 2in the functionset_to_2will not overwrite the value ofx;xis still 3. This goes for larger collections as well, such as lists or records (structs), which is not always enforced by all languages that appear to be pass by value (Python comes to mind).In Rust, however, we can pass by value, so the following is perfectly valid (albeit not exactly idiomatic):

fn set_to_2(n: &mut usize) { *n = 2; } let mut x = 3; set_to_2(&mut x);Luckily for us, Rust makes the fact that

xmay be overwritten perfectly clear, as you can see with the generous sprinkling ofmutused throughout the listing. Anyway, back to not copying things with every function call:

So, how do we overcome unnecessarily copying values before passing them to functions? With our good friend Copy on Write, of course! Recall our earlier example: a value passed via CoW to a function is not mutated, no copy is made. So as long as conswizzle is read-only, even if it’s called thousands times, no copies will be made:

big_list = [ ... ]

loop {

-- to the moon!

print (conswizzle big_list)

}

But what if mutations are made? We’ve addressed invariant #1:

All functions parameters are passed by value, via Copy on Write reference (CoW).

Now on to #2!

Static Single Assignment: Mutate on Last Use

If a function doesn’t mutate a list, it doesn’t copy it. Consider the following situation:

x = [ ... ]

x = modify_value x

print x

By the way: in Passerine, mutations can be made to values in their local scope. This is not altogether that dissimilar from a let-style redefinition, for those familiar.

So, just looking at this listing, it’s apparent that modify_value modifies x! Because [ ... ] will be passed as a CoW reference to modify_value, a copy of the list will be made, right?

Wrong. Let’s reintroduce Vaporization’s rule #2:

A form of SSA is performed so that the last usage of any value is that value itself, and is not CoW reference to that value.

SSA? What’s that? and how does it help?

Single Static Assignment (SSA) is a family of optimizations that have existed in compilers for about forever. It basically boils down to marking mutations to variables as separate variables. So, if we use a subscript notation to represent that a variable by the same name holds a different value, the above listing now looks like this:

x₀ = [ ... ]

x₁ = modify_value x₀

print x₁

Ok, so that’s the first part of SSA. What about the second part? Let’s annotate the last usage of each variable in the scope - we’ll do this by appending (') to the last occurrence:

x₀ = [ ... ]

x₁ = modify_value x₀'

print x₁'

At this point, I can see some of you smiling smugly in the back of the class.

Notice that the last occurrence of x₀' is passed to modify_value. After this point in time, by definition it is impossible for the program to reference the value of x₀.

Because this is the last usage of x₀, it doesn’t matter if we mutate it, etc. — which means, we can pass the value of x₀ to modify_value without wrapping it in a CoW reference first. Then, when modify_value modifies the unwrapped value, it will mutate x in place without making a copy.

I’ll reiterate this: the last usage of a value is always the value itself, so mutations to that value do not copy it. This means that from x = [ ... ] to print x, no copies of the big list are made! This is the foundation of functional-but-in-place programming. Even though we write our code in a functional pipelined manner, all modifications to the data will occur in-place.

Returning by Value

Only one reference.

Closures Capture

Aside: A Cyclic Problem

Why Closures Must be Immutable

Aside: Optimizing this away

TODO: stack charts and pull reference from comments on HN

Functional, but in Place (FBIP)

As far as I’m aware, this phrase originates from Koka, a programming language that focuses on algebraic effect handlers. Although Passerine doesn’t use the same automatic memory management strategy as Koka (which is called Perceus, btw), the same idea stands. From the Koka website:

With Perceus reuse analysis, we can write algorithms that dynamically adapt to use in-place mutation when possible (and use copying when used persistently). […] This style of programming leads to a new paradigm that we call FBIP: “functional but in place”. Just like tail-call optimization lets us describe loops in terms of regular function calls, reuse analysis lets us describe in-place mutating imperative algorithms in a purely functional way (and get persistence as well).

TODO: more