One day with Zig, Raylib, and jj

2024-12-25 · About 15 minutes long

Merry Christmas!

Back from the mission, first semester at MIT is in the books! Now I am at home, with family, on a break from school.

A couple days ago, I was telling my younger brother how cool Zig (the programming language) was. He was like, “if Zig is so cool, why don’t you … like, use it?” Oof. So I installed Zig, pulled in some neat bindings for raylib, and spent the afternoon writing a little interactive scrabble board demo to make sure that I understood what I was talking about (while he worked on some music for it, which I haven’t yet included):

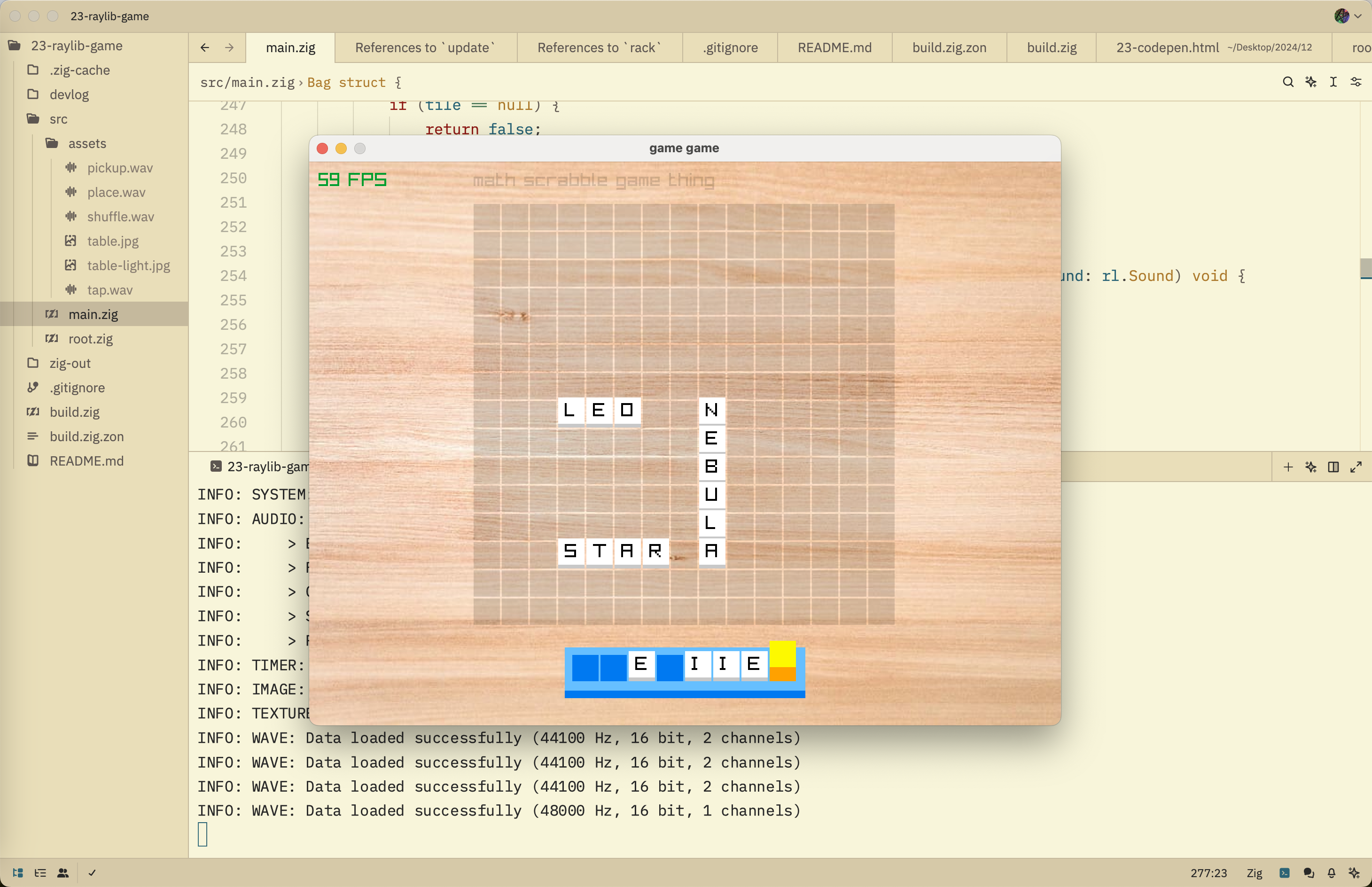

So that I can stop worrying about this project and lay it to rest, I decided to write a little blog post. The above demo doesn’t really work on mobile, and it may be broken (Wasm, JS, about 1MB in size, etc.), so here’s a screenshot:

When I showed my brother the demo, he was like, “that’s cool beta, but where’s the game?”

You can’t win every battle.

N.B. “Maybe if you made it a game you could” — my brother

Anyway, the code will be is now up on GitHub, it’s like ~500 lines and has like one dependency (raylib-zig) so it shouldn’t be too hard to get the native build working if you’d like to follow along then. The web build is a little hacky and left as an exercise to the reader.

Why Zig

I have been eyeballing Zig for a while. I think I first heard of the language via a talk Andrew Kelly gave at the recurse center … ah yep here it is: Software Should Be Perfect. 6 years ago, wow.

I really vibe with the language. From a language design PoV, generics through comptime functions is pretty fun. “Compiler as an interpreter over the static elements of the program” and all that. Also, I think @matklad has mentioned that there’s this goal of making Zig an incremental “real-time” compiler. Incrementally compiling code at 60 fps! Now that’s a goal I can get behind! From a tooling PoV, also very cool: I love the cross-compilation, and build.zig, while a bit to absorb all at once, is very useful and powerful, especially for e.g. embedding a C library like raylib.

I also came across the TigerStyle document out of TigerBeetle and it has changed the way I think about code. This project was for fun, but I can see how Zig can help scale the ideas in this document. It doesn’t try to hide anything from you. And like, aesthetically, I find the idea of e.g. statically allocating all memory up front to be very appealing.

Walk me through the code

I put the code up on GitHub, and I thought it would be fun to walk through some of it and point out some interesting stuff as we go along. Clone if you want to follow along!

N.B. I used jujutsu (jj) to do version control instead of git (without colocating) so I am figuring out whether I try to convert the jj repo to a git repo or just

git initandpushwithout any history. I’ll read the jj docs, there’s probably an easy way to export/convert/colocate.Update: Steve Klabnik, the Rust book guy (and now I guess also the jj tutorial guy?) pointed out on Lobsters that, because jj repos are backed by git repos, you can just add a remote and

jj git push. In brief detail, we can add a git remote:jj git remote add origin git@github.com:slightknack/scrabble.gitThen we can set a bookmark named

masterpointing at the most recent commit:jj bookmark set masterWhich we can then push to GitHub, the bookmark becoming the

masterbranch:jj git push --allow-newThe integration jj has with git is very cool! From the little time I’ve spent using jj and the lot of time I’ve spent reading about jj, I think that jj’s UI is much nice than git’s. On Lobsters, I observed that perhaps “jj is positioned to ameliorate the git world as TS ameliorated JS”. I’d like to live in that world; I’d better blog about jj more.

The approach I took to writing this project was essentially the approach that Casey Muratori outlines in his post Semantic Compression. I’m not going to explain it here, he does a much better job than I have space to. The core idea of this process is to add the next most obvious feature in the simplest way possible, not trying to abstract beforehand. Once a feature is working, gradually refactor out common ‘stack frames’ into structs, and functions that use those structs. Over time the codebase sort of organizes itself. I think this approach works really well when it comes to making game-like things, which makes sense: Muratori is a game programmer, after all.

N.B. I kinda missed the whole AI train (long story) so all this code was written by hand, reading the documentation (e.g. the entire Zig language is just one page!), etc. Mistakes are my own!

A note on comptime

I’d like to walk through the file and pull out interesting bits of code, just to give you a feel for the project, and maybe introduce some bits of Zig I found cool. The whole project largely exists in a single ~500 line main.zig file. At the top of the file, I have two imports:

const std = @import("std");

const rl = @import("raylib");

Two pretty cool items of language design, right away:

- A top-level

constlike this means that this code is evaluated at compile-time (comptime)! - Symbols starting with

@, like@import, are special to the compiler.@import("std")essentially adds a source file to the build, producing a struct, which we then can assign to a symbol, likestd. Neat!

We see this idea of comptime echoed a lot. Modules are just comptime structs in other files. Types are first-class values at comptime. Generics are functions that return types at comptime. And so on.

After our imports, we embed some static resources in the binary, sounds and textures:

const image_table = @embedFile("./assets/table-light.jpg");

const sound_place = @embedFile("./assets/place.wav");

const sound_pickup = @embedFile("./assets/pickup.wav");

const sound_tap = @embedFile("./assets/tap.wav");

const sound_shuffle = @embedFile("./assets/shuffle.wav");

The comptime function @embedFile is pretty cool, similar to the include_bytes! macro in Rust.

Structs and the shape of a stack frame

As I programmed, I ended up organizing game state into a few different structs, one generic:

Grid(rows, cols): fixed-size grid of squares, each square may contain a tile.Tile: A tile with a single letter on it.Rack: Contains aGrid(1, 7)and aButton, which can be used to refill the rack.Bag: Shuffles all 98 scrabble tiles and returns them one by one, similar to tetris.Button: A single button that can be clicked.

The Grid struct is generic. In Zig, this means it is a function that we call (at comptime!) with the number of rows and columns, to produce a concrete type with a statically-known size. We do this so we know how big of an array to allocate to hold all the tiles in the grid. I’m actually rather proud of this fact: by virtue of never using an allocator, this code never allocates on the heap! (Caveat, raylib internals.) Here’s how Grid is defined:

fn Grid(

comptime num_rows: usize,

comptime num_cols: usize,

) type {

return struct {

const Self = @This();

rows: usize = num_rows,

cols: usize = num_cols,

posX: i32,

posY: i32,

tile_width: i32,

tile_height: i32,

gap: i32,

// like some text in a book, left to right, top to bottom

tiles: [num_rows * num_cols]?Tile,

// methods, etc. ...

}

}

Raylib is essentially an immediate mode library for graphics. Meaning, each frame, we have to generate a sequence of draw events that will produce the picture we see on the screen. Each of the above structs (except for Bag) has an update method and a draw method that can be called each frame. It’s refreshingly simple.

Again, I wrote the code in a procedural style and ‘pulled out stack frames’ as I went along. I wasn’t trying to take an object-oriented approach, or confine structs to a given interface. These were the patterns that emerged in the code that I pulled out of main.

I don’t know why, but I find this to be such a fun way to code. Here’s the method that draws the grid, for example:

/// draw the grid background and all the tiles on the grid

fn draw(

self: Self,

color: rl.Color,

) void {

// draw the grid background

for (0..self.rows) |row| {

for (0..self.cols) |col| {

const r: i32 = @intCast(row);

const c: i32 = @intCast(col);

rl.drawRectangle(

self.posX + c * self.tile_width,

self.posY + r * self.tile_height,

self.width(),

self.height(),

color,

);

}

}

// draw the tiles on top

for (self.tiles) |maybe_tile| {

if (maybe_tile) |tile| {

tile.draw(rl.Color.white, rl.Color.light_gray, rl.Color.black);

}

}

}

Isn’t that so … satisfying? I mean sure, it’s not a beautiful Haskell one-liner, yet it contains exactly everything that needs to happen, no less, and no more.

N.B. I also really love Zig’s block syntax

|...| { ... }forforandif. The way Zig does nulls is very cool and I’ll have to write about it some more sometime.

The way I did tiles is pretty fun. Here’s a Tile:

const Tile = struct {

pos: rl.Vector2,

width: i32,

height: i32,

hover: f32,

thick: i32,

letter: u8,

// ...

}

Note that rl.Vector2 is a type defined by raylib (rl) and essentially amounts to two f32s. Elsewhere, hover is the height the tile is floating above the ground, and letter is a byte representing the ASCII code for the letter on the tile.

Animations falling into place

What’s really great is how naturally the tile animations fall out of this. When we place a Tile in a Grid, the grid stores it in a linearized array, Grid.tiles:

// like some text in a book, left to right, top to bottom

tiles: [num_rows * num_cols]?Tile,

When we update the grid each frame, we animate each tile in tiles towards the resting position it should be in. Here’s what that looks like:

/// animate placed tiles towards their resting grid positions. should be called once per frame.

fn update(self: *Self) void {

for (0..self.rows) |row| {

for (0..self.cols) |col| {

const r: i32 = @intCast(col);

const c: i32 = @intCast(row);

// guaranteed to be within bounds

const index = self.toIndex(r, c).?;

const target = self.toTarget(r, c);

var tile = &(self.tiles[index] orelse continue);

tile.settleInPlace(target);

}

}

}

I have no clue whether there’s a better way to get a reference to tile than the approach I used. Surely there is, compared to this:

var tile = &(self.tiles[index] orelse continue);

tile.settleInPlace(target);

We have an array of optional tiles ([]?Tile) and a reference to an item in that array is a *?Tile, but we need a *Tile. I had fun here but there’s probably a very simple way to do this. I digress

We go through each tile and nudge it towards where it needs to be on the grid. The method tile.settleInPlace just nudges the tile towards the target position, and lowers the hovering tile to the ground:

/// animate the tile towards a given target. should be called once per frame

fn settleInPlace(self: *Tile, target: rl.Vector2) void {

self.pos = rl.math.vector2Lerp(self.pos, target, 0.3);

self.hover = rl.math.lerp(self.hover, 0.0, 0.08);

}

Here lerp is a classic trick older than time. I’m sure other people have their own names for this, but I don’t think it needs a name. I think of it as the pos += (target - pos) / speed trick. In the APL tradition, if something is simple enough that it is about as long as its name, why name it?

We use a similar trick for when a tile is hovering over a grid. We want the tile to be “magnetically attracted” to the grid spaces but also follow the mouse. We can use the tension between two lerps to make that happen:

/// animate the tile towards the mouse, biased towards the grid. should be called once per frame.

fn followMouse(self: *Tile, mouse: rl.Vector2, snap: rl.Vector2) void {

const pos_mouse = rl.math.vector2Lerp(self.pos, mouse, 0.1);

const pos_snap = rl.math.vector2Lerp(pos_mouse, snap, 0.2);

self.pos = pos_snap;

}

The parameter snap is computed elsewhere, but it’s the screenspace coordinates of the nearest grid cell.

N.B. I was considering keeping track of velocities to make the tile springy and give it some mass (another classic trick). Here’s what that looks like, if curious

vel += vel * friction + (target - pos) / speed pos += vel

What is really cool about this procedural stateless approach to animating tiles is that when we add a tile to a grid, or have it follow the mouse, it naturally smoothly travels to the right place. Complex dynamic behaviour is best driven by simple behavior compounded over time.

Randomness and the bag

One thing I wanted to get right was the Bag. I didn’t want to allocate anything, but I wanted the distribution of scrabble tiles to be correct. Well, the second part is easy, we just need a bag with each tile:

/// don't ask

const scrabble_bag: *const [98:0]u8 = "EEEEEEEEEEEEAAAAAAAAAIIIIIIIIIOOOOOOOONNNNNNRRRRRRTTTTTTLLLLSSSSUUUUDDDDGGGBBCCMMPPFFHHVVWWYYKXJQZ";

We’ll just allocate, on the stack I suppose, a single large struct with space to hold all these letters:

const Bag = struct {

scrambled: [98]u8,

next: usize,

// ...

}

N.B. I don’t know how Zig internally deals with large structs like this. I know that, in principle, when a function is called, structs are passed by value, “making a fresh immutable copy”. I would hope that in practice Zig optimizes this to a reference to an earlier stack frame or similar.

All we’ll do is shuffle our scrabble_bag into Bag.scrambled, then empty out the bag by incrementing next, shuffling again when we reach the end. Oh. How does one shuffle in Zig? I will note that this was a little non-trivial to find docs for because there is a deprecated API that shows up higher in the search results, but the long story short is we want to use std.Random via std.crypto.random, and that’s something you can look up.

Here’s the code that shuffles the bag:

fn fresh() Bag {

const rand = std.crypto.random;

var loc: [98]u8 = scrabble_bag.*;

rand.shuffle(u8, &loc);

return Bag{

.scrambled = loc,

.next = 0,

};

}

Figuring out var loc: [98]u8 also took a little work. Zig doesn’t have full Hindley-Milner type inference, as Rust does. Sometimes you have to guide the compiler along by using @as or explicit bindings. Not necessarily a bad thing, it’s good to know what types are flowing through the program. A good balance between Rust’s type inference magic and Austral’s purposeful lack thereof.

N.B. This makes total sense, in the context of Zig’s comptime! When generic types are built function calls, type information flows in one direction. Flowing program information backwards is what we see in languages like Prolog, where rules can be thought of as bidirectional functions. I briefly explored this direction in a compiler I am working on, which has (had?) first-class support for datalog-like queries. “Type inference as a comptime datalog query.” Maybe someday.

Okay, and just for completion’s sake, here’s the rest of Bag:

/// pick a tile from the bag. if the bag is empty, replace with a fresh bag.

fn pick(self: *Bag) u8 {

const drawn = self.scrambled[self.next];

self.next += 1;

if (self.next >= self.scrambled.len) {

self.* = Bag.fresh();

}

return drawn;

}

I was surprised that std.crypto.random worked out of the box for the wasm build of the demo. From my experience with Rust and rand, this is not always something that automatically works.

My main man

We’ve already talked about most of the project, structured as follows:

- Imports and embeddings

- Structs and methods

- The

mainfunction- Startup code

- Per-frame loop

I’d like to talk about the main function, because it’s the beating heart of this whole thing. As I mentioned, I wrote this project by writing a main function, and then pulling out functions and bundles of local variables as things got repetitive. So main really is the driver of the whole codebase, both literally and conceptually.

Raylib is delightful to work with. Here’s how we set up our window:

pub fn main() anyerror!void {

const screenWidth = 800;

const screenHeight = 600;

rl.initWindow(screenWidth, screenHeight, "game game");

rl.initAudioDevice();

rl.setTargetFPS(60);

defer rl.closeWindow();

defer rl.closeAudioDevice();

// Startup code and per-frame loop

}

I love how I can use defer here. It’s a nice way to pair together functions that must be called together, but at different times. A lot of old C APIs expect this sort of “manual nesting by the programmer” to enter and exit over e.g. taking a callback. I prefer defer over RAII, though. At least in this context: raylib is simple and global and single-threaded, what do I know.

The startup code that comes after builds a lot of structs. It looks like this:

var grid = GridBoard{

.posX = 175,

.posY = 45,

.tile_width = 30,

.tile_height = 30,

.gap = 2,

.tiles = [_]?Tile{null} ** (15 * 15),

};

// more structs

I considered factoring this out into a bunch of unique init functions, but that’s like squeezing a water balloon. The lines are just going to pop up somewhere else in the codebase, and I’d rather have all this initialization code in the same place for easy tweaking. Maybe if the project were bigger.

Then we load all the sound and image data for the game. Remember, this was embedded into the binary earlier with @embedFile. Honestly I am so impressed by how nice and logically organized raylib’s API is, what a treat:

const image_table_mem = rl.loadImageFromMemory(".jpg", image_table);

const image_table_tex = rl.loadTextureFromImage(image_table_mem);

const sound_pickup_mem = rl.loadWaveFromMemory(".wav", sound_pickup);

const sound_place_mem = rl.loadWaveFromMemory(".wav", sound_place);

const sound_tap_mem = rl.loadWaveFromMemory(".wav", sound_tap);

const sound_shuffle_mem = rl.loadWaveFromMemory(".wav", sound_shuffle);

const sound_pickup_wav = rl.loadSoundFromWave(sound_pickup_mem);

const sound_place_wav = rl.loadSoundFromWave(sound_place_mem);

const sound_tap_wav = rl.loadSoundFromWave(sound_tap_mem);

const sound_shuffle_wav = rl.loadSoundFromWave(sound_shuffle_mem);

// per-frame loop.

If only I were better at naming things, haha.

Onto the per-frame loop. We start by clearing and drawing the background. Another useful appearance of defer:

while (!rl.windowShouldClose()) {

rl.beginDrawing();

defer rl.endDrawing();

rl.clearBackground(rl.Color.white);

rl.drawTexture(image_table_tex, 0, 0, rl.Color.white);

defer rl.drawFPS(10, 10);

// ... update and draw

}

I wanted to draw the FPS counter on top of everything, which I can do by drawing it last through defer.

There’s a lot of pretty dense game state updating that I don’t want to bore you with, but it’s nothing complicated. I probably should break it up into a few functions. Here’s how we update and draw the grid:

grid.update();

grid.draw(rl.Color.dark_brown.alpha(0.2));

And to give you an idea of the logic, here’s the logic for trying to pick up a tile:

if (mouse_click) {

if (grid.pickUp(tile.pos)) |got_tile| {

tile = got_tile;

tile_visible = true;

rl.playSound(sound_place_wav);

} else if (rack.grid.pickUp(tile.pos)) |got_tile| {

tile = got_tile;

tile_visible = true;

rl.playSound(sound_pickup_wav);

}

}

There’s similar code for placing a tile, how to swap a tile, updating the tile to follow the mouse, and so on.

Again, look at that beautiful raylib API for playing a sound!

Final thoughts

I had a lot of fun messing around with Zig and raylib!

I really do enjoy picking up new tools like this. Trying out a project like this is low stakes, and experience is the best teacher. I have read a lot of Zig code, but this is the first time I really write something. Thank you Andrew Kelley and everyone who works on Zig and, well, @raysan5 for raylib (and @Not-Nik for the bindings)!

One thing I missed coming from Rust was pattern matching. Zig doesn’t have pattern matching, I suppose? Reading some discussion online, it seems to be that Zig’s switch statement—the moral equivalent to Rust’s match—compiles to a jump table, but pattern matching can lead to non-obvious control flow. I can see how that goes against the ethos of Zig, but man pattern matching would be nice. Maybe there’s a library that emulates pattern matching? Could a library generate pattern matching code at comptime? Who knows!

I don’t know if I will add more to this game, but if I do, stay tuned. I have been thinking about what it would take to add online multiplayer. I have also been sketching out a fun little CRDT library. We’ll see what happens.

Oh yeah! and I totally forgot to touch on build.zig! I’ll have to touch on that the next time I write about Zig.

And jujutsu was really fun. I even got to use amend. Another topic for another post!

Merry Christmas, and to all a good night!

Padded so you can keep scrolling. I know. I love you. How about we take you back up to the top of this page?